Explicit and Implicit Collaborative Filtering

There are several situations when we may want to recommend a product or a piece of content to a user in order to increase our revenue, the engagement of the user with our site or the value perceived by the user while experiencing our site. We cannot recommend items that the user has already left a review on, as he or she has already seen the product and is well-aware of its features. Therefore, we must adventure and try to estimate which items of our catalog are the ones that the user might be interested in, without having an explicit signal for that particular item/user combination.

This is where Collaborative Filtering (CF) comes in. Collaborative Filtering is a technique that allows us to estimate the interest of a user to a set of items. The idea is that we can use the reviews of other users to estimate the interest of a different user on the items that those first users reviewed. It is similar to say:

“Person A liked products X, Y and Z. Person B liked products X and Z. Therefore, B might like Y with a reasonable confidence.”.

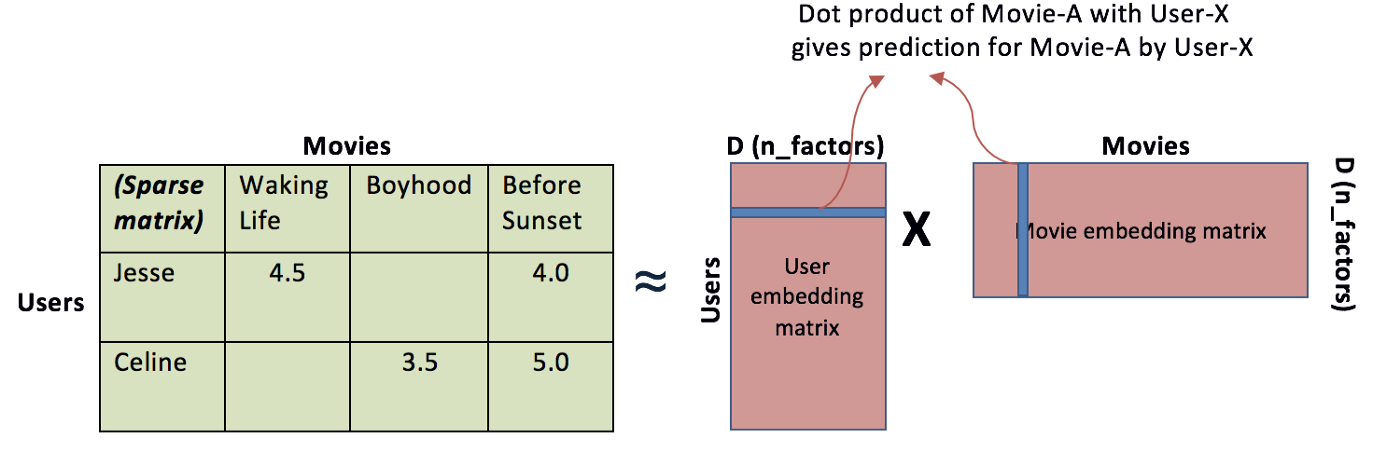

This interesting and intuitive process is done by assigning $K$ latent features for each item, and then infer for both the users and the items each of these features so we can see how the user and the item are related. These latent factors can be imagined as the implicit features that our items have, such as the “recentness” of an item in the market, how eco-friendly it is or how related is to a particular topic, such as culture or health, but in the end they are just vectors that are optimized to minimize a cost function, similarly as it happens with word embeddings in NLP tasks.

In order to make these predictions and approximate the users preferences successfully we must check the data available and thus the restrictions of the models we may develop to help us with the task at hand. Depending on the data we have, there are two main branches of collaborative filtering models:

- Explicit Collaborative Filtering, which are the most common models, and the ones that are ancient and proven by the research community. To apply them we need an abundance of explicit scores on the user/item combinations, such a rating from 1 to 5 stars or a good/bad review.

- Implicit Collaborative Filtering, which are models trained without any explicit score at a user/item level. To apply them we use the signals left by the user on our sites, such as the item page views, the add-to-cart events or the purchases of the user.

Explicit Collaborative Filtering

For an example of Explicit Collaborative Filtering please check this repository: MovieLens Recommender

As we mentioned before, the explicit collaborative filtering models are the ones that try to predict a known variable, which could be a continuous value as a rating from 1 to 5 stars or a categorical value as a good/bad review. Thus, we face a supervised learning problem, given a matrix X of user/item combinations and a vector y of explicit scores, and depending on the form of the scores we will be using a regressor or a classifier. Now that we know the kind of problem we are facing, it is simpler to come up with good solutions to solve it, so let’s explore a few.

Classic Collaborative Filtering

A few years back, when Deep Learning was not still as popular as it is and computational resources were scarce, we had to use a very simple model to predict the ratings of our users. Although, this primordial model was not bad at all, and it served as foundation to the vast majority of the newer models. This model was simply called Collaborative Filtering and it was based on the random assignment of $K$ latent factors for the matrices of users and items, and then use those matrices to infer the ratings of the users to the items by multiplying them. After that, we could compute our loss depending on the kind of label we have (either MSE for regression or crossentropy for classification, for example) and if the score was off then we could use an optimizer such as SGD to adjust the latent factors to the correct value. Then, we would compute again the ratings of the users to the items, finishing our training cycle.

If we want a more in depth view of classic collaborative filtering, this video by Andrew Ng is an invaluable resource.

We can apply this method using simple NumPy, but as it is based on linear algebra and we might want to take advantage of our GPUs let’s see an example using PyTorch:

class Recommender(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, n_users, n_movies, emb_size, y_range):

super(Recommender, self).__init__()

self.user_embedding = nn.Embedding(n_users, emb_size)

self.user_bias = nn.Embedding(n_users, 1)

self.movie_embedding = nn.Embedding(n_movies, emb_size)

self.movie_bias = nn.Embedding(n_movies, 1)

self.y_range = torch.tensor([[y_range]], dtype=torch.float)

def forward(self, x):

users = self.user_embedding(x[:, 0])

movies = self.movie_embedding(x[:, 1])

result = (users * movies).sum(dim=1, keepdim=True)

result += result + self.user_bias(x[:, 0]) + self.movie_bias(x[:, 1])

return result.clip(min=y_range[0], max=y_range[1])

As we can see, we instantiate both the weights and biases for each user and item and then simply multiply their weight matrices together. We also add the bias to the result of the multiplication, and we clip the result to the range of the ratings we have in order to make our network converge faster. We could instantiate and train the model using this snippet of code:

def train_model(model, loader, epochs, optimizer, criterion):

model.train()

for i in range(epochs):

print(f"Starting epoch {i}...")

for x, y in loader:

y_hat = model(x)

optimizer.zero_grad()

loss = criterion(y_hat, y.unsqueeze(1))

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

print(f"Loss obtained: {loss.item()}")

n_users = df.userId.max() + 1

n_movies = df.movieId.max() + 1

emb_size = 50

y_range = (0.5, 5)

model = Recommender(n_users, n_movies, emb_size, y_range)

model = model.to(device)

optimizer = optim.Adam(model.parameters(), learning_rate)

criterion = nn.MSELoss()

train_model(model, train_loader, 25, optimizer, criterion)

Despite its simplicity, this model should be able to predict the ratings of our users with a decent error if we tune the number of latent factors and the learning rate accordingly, although in the end it’s just a linear model and it has its drawbacks and limitations, so let’s see how we can build upon it.

Deep Collaborative Filtering

Breakthroughs as the adoption of GPUs by the deep learning community, the availability of immense quantities of data and new parameter initialization techniques or activation functions have awaken a new wave of interest in the field of deep learning and neural networks. This also apply to the field of recommender systems, as thousands of websites can make use of better recommendations for their users.

Enter the feed-forward collaborative filtering models, which build upon the latent factors of the classic collaborative filtering models by adding several layers on top of them. These layers allow our models to find deeper and more complicated relationships between the users and the items, and thus, to predict the ratings of the users to the items with a better accuracy. It is important to mind that these models are nothing but an application of the ideas previously seen, which are sometimes more than enough to provide good recommendations, and that they come with a higher computational cost, so it may be wise to test first a simpler model and then iterate upon it.

Continuing our PyTorch code, we now will see how to build this kind of models:

class FFRecommender(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, n_users, n_movies, emb_size, n_units, dropout, y_range):

super(FFRecommender, self).__init__()

self.user_embedding = nn.Embedding(n_users, emb_size)

self.movie_embedding = nn.Embedding(n_movies, emb_size)

self.linear1 = nn.Linear(emb_size * 2, n_units)

self.linear2 = nn.Linear(n_units, 1)

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(dropout)

self.y_range = torch.tensor([[y_range]], dtype=torch.float)

def forward(self, x):

users = self.user_embedding(x[:, 0])

movies = self.movie_embedding(x[:, 1])

h1 = nn.functional.relu(self.linear1(torch.cat([users, movies], 1)))

h1 = self.dropout(h1)

result = self.linear2(h1)

return result.clip(min=y_range[0], max=y_range[1])

The additions to the code come as linear layers. We also added a dropout layer as regularization and drop the matrix multiplication, as PyTorch’s nn.Linear does that for us. In this occasion, the code to instantiate and train the model is very similar to the one we used for the classic collaborative filtering model:

n_units = 100

dropout = 0.2

ff_model = FFRecommender(n_users, n_movies, emb_size, n_units, dropout, y_range)

ff_model = ff_model.to(device)

optimizer = optim.Adam(ff_model.parameters(), learning_rate)

criterion = nn.MSELoss()

train_model(ff_model, train_loader, 25, optimizer, criterion)

These models are expected to reach a better score than the previous ones due to their higher complexity, although it comes at a cost in form of more hyperparameters to tune and higher computational cost.

Sequential Collaborative Filtering

Continuing our journey down the rabbit hole of neural networks, we can now build a sequential collaborative filtering model. This model is a combination of the feed-forward and the recurrent models, which allow us to think of user preferences not as a fixed vector at a user level but more as a sequence based tensor that depends on the particularities of the items reviewed and their order. The idea behind this model is to capture the effect of recent reviews of users on the next item to be scored as, for instance, a user may decrease the score of a romance movie if he or she has only been watching this genre of movies lately and grew tired of them.

On most of the occasions, our data will be in a tabular form, so we may need first to convert them to sequences to pass through our model:

sequences = []

for userId in df_train.userId.unique():

df_filtered = df[df['userId'] == userId].sort_values(by='timestamp')

user_sequence = (df_filtered['movieId'].values[:10], df_filtered['rating'].values[:10])

sequences.append(user_sequence)

cutoff_index = int(len(sequences) * 0.8)

sequences_train, sequences_test = sequences[:cutoff_index], sequences[cutoff_index:]

Now that we created the sequences to serve to our model, we may use Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) to implement this solution. The most common RNNs are LSTMs and GRUs, and due to its higher complexity and popularity we will be using LSTMs here:

For a more in depth explanation of RNNs, please refer to this video by MIT.

class SeqRecommender(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, embedding_dim, hidden_dim, num_items, num_output):

super().__init__()

self.hidden_dim = hidden_dim

self.item_embeddings = nn.Embedding(num_items, embedding_dim)

self.lstm = nn.LSTM(embedding_dim, hidden_dim)

self.linear = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, num_output)

self.hidden = self.init_hidden()

def init_hidden(self):

# initialize both hidden layers

return (torch.autograd.Variable(torch.zeros(1, 1, self.hidden_dim)),

torch.autograd.Variable(torch.zeros(1, 1, self.hidden_dim)))

def forward(self, sequence):

embeddings = self.item_embeddings(sequence)

output, self.hidden = self.lstm(embeddings.view(len(sequence), 1, -1),

self.hidden)

rating_scores = self.linear(output.view(len(sequence), -1))

return rating_scores

def predict(self, sequence):

rating_scores = self.forward(sequence)

return rating_scores

Regarding the training of our model, we may again see that the code is quite similar:

n_units_lstm = 30

seq_model = SeqRecommender(emb_size, n_units_lstm, n_movies, 1)

criterion = nn.MSELoss()

optimizer = optim.Adam(seq_model.parameters(), learning_rate)

seq_model.train()

for epoch in range(25):

for sequence, target_ratings in sequences_train:

seq_model.zero_grad()

seq_model.hidden = seq_model.init_hidden()

sequence_var = torch.autograd.Variable(torch.LongTensor(sequence.astype('int64')))

ratings_scores = seq_model(sequence_var)

target_ratings_var = torch.autograd.Variable(torch.FloatTensor(target_ratings.astype('float32')))

loss = criterion(ratings_scores, target_ratings_var.view(10, 1))

loss.backward(retain_graph=True)

optimizer.step()

print(f"Loss obtained on epoch {epoch+1}: {loss.item()}")

In case we want to make our model more complex, we may want to add a second layer of LSTM to the model, or a second linear layer after the first one. Nevertheless, I still recommend using first a simpler model, evaluate the results and build add more layers to it if necessary.

Implicit Collaborative Filtering

We can see the code of a practical example on this kind of tasks here: Retail Rocket Recommender

The methods for Explicit Collaborative Filtering are straight-forward, effective and widely used by industry peers. Nevertheless, they require many data points of users explicitly informing us of how aligned a particular item is to their interests, which cannot always be obtained easily due to restrictions in our website or legal issues, for instance. We mentioned in the beginning of this article that there are methods to deal with training collaborative filtering models on implicit datasets, and we will see the most renowned one: Alternating Least Squares.

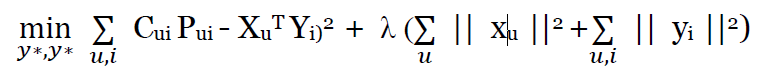

The Alternating Least Squares (ALS) method was first reviewed by Yifan Hu et al and describes the use of a confidence matrix composed by the aggregated signal of the events a particular user generated while interacting with a certain product to infer the preference matrix, which is the binary version of the previous matrix and determines if a user has a preference for a particular product or not. Once we have the preference matrix, we compare it with the dot product of the latent factors of our users and items and weight that score by multiplying the confidence matrix, so the combinations with more signal are the ones that add more to the cost. Lastly, we will also be including a regularization parameter $\lambda$ which will help us avoid overfitting using a similar technique to L2 regularization. In this kind of models we have to avoid overfitting as much as possible as it would lead our estimators to only repeat the combinations seen previously in the training data.

Using a business case of an e-commerce trying to give their users the most adequate recommendations, we could apply ALS by first computing our confidence matrix, weighting the different signals of the user/item interactions to a single value. We will use for this case the following signals:

- Product Page views, which will score as 1 in our confidence matrix.

- Add-to-cart events, which will score as 5.

- Transaction events, which will score as 25.

With the difference on scores for each signal we expect to prioritize the strongest events above more frequent ones which may be deceiving, such as the page views. We can use Python to compute this confidence matrix easily given those weights:

df['event_scores'] = df['event'].apply(

lambda x: 1 if x == 'view' else 5 if x == 'addtocart' else 25 if x == 'transaction' else 0

)

Later on, we make this matrix sparse, as it’s mostly composed by 0s and this conversion will speed up training and save us a lot of memory space that in cases with thousands of products and clients might be critical:

df['visitorid'] = df['visitorid'].astype("category").cat.as_ordered()

df['itemid'] = df['itemid'].astype("category").cat.as_ordered()

sparse_item_user = sparse.csr_matrix((df['event_scores'].astype(float), (df['itemid'], df['visitorid'])))

sparse_user_item = sparse.csr_matrix((df['event_scores'].astype(float), (df['visitorid'], df['itemid'])))

Once the matrix is built and on a sparse form, we may simply use the ALS implementation of the library implicit to infer the latent factors of our items and users.

P.S: Although ALS is the most common method for implicit recommendations, the

implicitlibrary has implementations for the rest of algorithms available for this task. If you are curious about them please go ahead and visit its documentation.

latent_factors = 20

regularization = 0.1

n_iter = 20

alpha = 40

conf_matrix = (sparse_item_user * alpha).astype('double')

model = implicit.als.AlternatingLeastSquares(

factors=latent_factors,

regularization=regularization,

iterations=n_iter

)

model.fit(conf_matrix)

Et voilà!, our model is trained and ready to make suggestions for our users. Not only that, but we can also see which products are most similar among them, so we can infer substitute items in case of stock outs or to suggest products that solve the same needs but provide us a higher margin. The code for both this use cases would be the following:

def recommend_item_to_user(model, visitorid, sparse_item_user, n=10):

recommended = model.recommend(visitorid, sparse_item_user[visitorid], n)

return recommended

def similar_items_to_item(model, itemid, n=10):

similar = model.similar_items(itemid, n)

return similar

And we can call these functions as we would do with any Python module:

# Choose an userid

userid = 97154

recommended_items = recommend_item_to_user(model, userid, sparse_item_user)

print(f"Recommended items for user {userid}:\n{recommended_items[0]}")

# Choose an itemid

itemid = 350566

similar_items = similar_items_to_item(model, itemid)

print(f"Similar items to {itemid}:\n{similar_items[0]}")

Conclusions

In this post we were able to see in detail the main mechanism behind the recommendations we often see on sites as Netflix, Amazon or Alibaba and apply different techniques to increase their capabilities or apply regularization layers as Dropout on them. We also saw how to deal with not having a good enough explicit dataset by using the signals left by our users in our site such as the purchases or the page views to infer their preferences.

Hope this was useful and in case you have any doubt about the concepts explained on this article please do not hesitate to connect with me to further discussions. Thank you and keep on learning!